When the first hang glider pilots came to the Owens Valley in the early 1970’s, they were regarded by knowledgable aviators as utterly and suicidally insane. They were certain that in this place that spawned the greatest measured turbulence in the world, the madmen on the featherlight fabric wings would surely be killed. But they would be proved wrong. Owens Valley was destined to become Hang Glider Heaven.

The discovery is unforgettable.

As the hiker climbs eastward, the broad expanse of the fertile San Joaquin Valley drops slowly away. Far to the west, rising out of the valley haze, the gentle peaks of the coastal mountains appear. Suddenly the forest of pine gives way to a grove of towering Sequoia, the most gigantic of trees.

Onward he goes, upward, following the raging Kern River to the granite-walled canyons of its birth in the heart of the Sierra Nevada. Now the highest peaks can be seen, their flanks rising precipitously from the river itself. The trail becomes steep and narrow, at times cut into sheer rock where a misstep means death. The struggle seems endless. Breath comes short at this altitude. Then, in an instant, it is over.

The mountains stop.

As if cut by a knife, they plunge as one to the floor of the Owens Valley. Stretching two hundred kilometers northward, the massive granite escarpment marks the path of the Sierra Nevada fault where, in ages past, the Kern Plateau was ripped asunder to form the Owens Valley.

To the south, Owens Dry Lake, barren as the moon, shimmers and glares a red-rimmed eye in the desert heat. Out of the lake bed, towering dust storms race along the base of the desolate Inyo Range. Beyond, to the east, the desert mountain ranges march in rows across the Great Basin. Their names, given by men who crossed them on foot a hundred years ago, offer a lasting warning to the future unwary traveller: the Last Chance, Death Valley, Skull Mountain, Funeral Peak and the Dead Range.

The Inyos merge with the White Mountains to the north, where awesome Boundary Peak, highest point in Nevada, marks the end of the range. The shattered remains of a monstrous volcano, Glass Mountain, fills the north end of the valley, resting against the Sierra and almost touching the White Mountains. The narrow corridor that remains is the spawning ground of immense, sinuous dust devils often two kilometers high.

Owens Valley is claimed to be the deepest valley on earth, yet in another way it is even more superlative. Winter winds in concert with the jet stream deflect upward from the Sierra Nevada to form the most extraordinary atmospheric wave condition known. Three distinct cloud types appear at this time. The foehn drives the cap clouds down the escarpment like a waterfall, while high above, the wave cloud runs the length of the valley in a curvilinear streak. Between these writhes the deadly roll cloud, constantly forming on its upwind side and dissipating downwind, boiling and dark, often rotating. Caught in the first rotor of the sinusoidal wave system, its turbulence rivals that of the interior if the cumulonimbus.

The first man to die in the wave was a European sailplane pilot. In pursuit of a world altitude record, he rode the wave to a height of eleven kilometers. There, photos from his hand-held camera found in the wreckage indicate, his oxygen system froze. He didn’t notice and lost consciousness. The sailplane entered a spin and crashed near Independence.

The roll cloud offers an even more exciting way to die. In 1959 a sailplane pilot was pulled into a roll cloud above Bishop. Although he was flying one of the world’s strongest sailplanes, a Pratt Read, the vicious turbulence snapped a wing and broke the fuselage to pieces. Ripped from his seat harness with a broken shoulder, his helmet, boots, oxygen mask and gloves torn from him, he fell unconscious, into the roll cloud. He regained consciousness in free-fall to discover he was blind. Stunned, fearful he would impact the ground at any moment, he cast his parachute into the swirling madness of the cloud. It opened with such force that many shroud lines parted and his boots were lost .

Helpless and swinging wildly beneath his canopy, he realized he was trapped within the cloud. After half an hour, his sight returned to the point where he could see pieces of his sailplane being carried upward past him. Miraculously, he escaped the cloud, but only to be blown toward the jagged cliffs of the White Mountains. Summoning his last reserves of strength, he spilled air from his canopy, using his good arm, and brought himself down.

The first hang gliding flight was made from the top of the White Mountains on September 23, 1973. The man who stood beneath the flapping rogollo had flown sailplanes. He knew about thermals and turbulence. He and his close friends, the Wills brothers, were pioneering the rebirth of hang gliding. He felt superbly confident in his ability to fly. At 23, Chris Price was a master of the sailwing. And he knew it.

What he didn’t know was that across the valley an atmospheric wave had formed above the Sierra Nevada. It crested high above the range and dove down into the valley, only to be deflected upward by the great Whites to form a secondary wave. Above the highest peaks, dwarf wave clouds struggled to exist in the drying, desert-bound air while in the valley the invisible wave rotor swirled and writhed in the depths of the trough.

He ran but the steps were not necessary. The wind plucked him up like a feather. Suddenly he was high above the ridge and drifting backwards! He pulled his weight forward until the control bar was touching his knees. He stopped drifting back, but he could not penetrate into the wind. He crabbed to the south, searching for weaker conditions.

He flew into a powerful downdraft. The jagged ridges leapt toward him. Then the glider’s nose pitched upward and his harness straps strained as the sink changed suddenly to strong lift. It was all he could do to keep the glider pointed out into the valley. But gradually Chris made progress. He moved awayfrom the mountains and escaped the intense upper winds.

When it came time to land, he set a high approach and touched the glider down on the shoulder of the alluvial fan just above the little town of Chalfant. He unhooked, stepped to the front of the glider, and looked up. Above the highway, not a mile down the sloping alluvium:, the ghostly outline of a deadly rotor cloud spun lazily against the deep blue sky. A chill ran through him.

Only a few hang glider pilots, all from California, came to the Owens Valley over the next two years. Don Partridge of Bishop was launching from the Sierra escarpment in 1974, but a flight into turbulence dampened Don’s enthusiasm for high altitude flight as he watched the wires of the Chandelle Rogallo snap taut and slacken, and his leading edges flex a kilometer above the valley floor.

Even without the presence of the wave, pilots would discover that each Owens Valley site presented its own peculiar dangers. Rich Grigsby and Trip Mellinger flew off the Whites east of Bishop to encounter tremendous sink over rugged Silver Canyon. They were forced to land between the sheer granite walls and the rows of power lines that fill the canyon.

Partridge and Steve Huckert launched their standard Rogallos from two-kilometer-high Coyote on the Sierra west of Bishop to discover that the wind they had launched into was actually the underside of the monstrous Sierra Nevada rotor. Steve was thrown through his flying wires and his craft spun almost to the ground before he managed to recover. Don experienced a seemingly endless series of tail-sliding stalls in teeth-rattling turbulence. Somehow, they made it down alive.

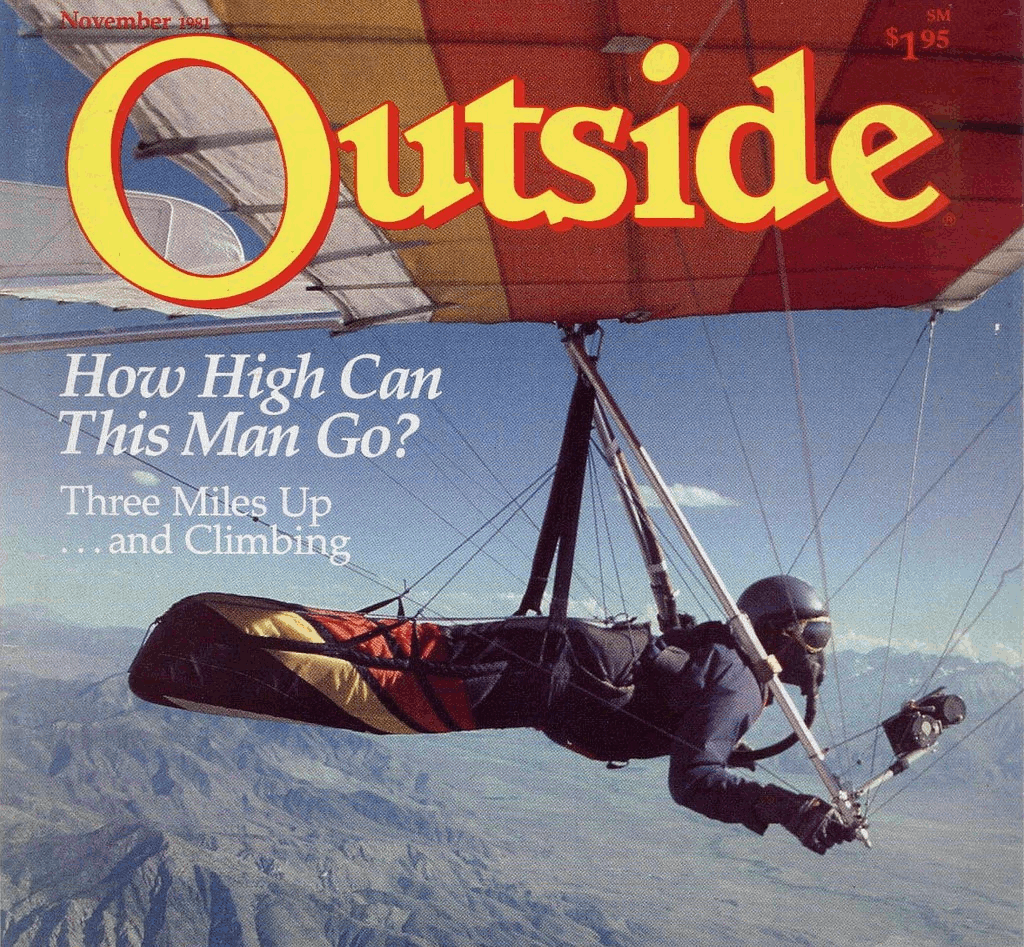

In July of 1976, Gene Blythe and Trip Mellinger set unofficial world records for distance and altitude after a series of flights from the southernmost launch on the Inyos, Cerro Gordo. When champion sailplane pilot George Worthington learned of this, he became intrigued with the idea of capturing all the official records for hang gliding newly recognized by the FAI. The following summer, he did just that.

Don Partridge flew with George all that summer. George’s achievements inspired Don with the idea of the first true cross country hang gliding competitions. Don sent out invitations to the best pilots he knew announcing a contest in the summer of 1978. Forty-six pilots came to the first Cross Country Classic.

“You could feel the fear,” Don said, “from people wondering, ‘Can hang gliders really fly in afternoon turbulence in Owens Valley?’ …. If these things can actually fly in this place, the most turbulent place on earth, in the most turbulent time of day, then they’re going to prove themselves as worthy aircraft. Otherwise they’re just toys.”

Bill Bennett of Delta Wing Kites, the world’s leading hang gliding manufacturer, sent a team of six to fly Dick Boone‘s newly designed, high performance Mariah in the contest. By the third day they pulled far ahead in the standings. But then the team leader got into trouble above White Mountain Peak.

To gain a little more speed from his Mariah, Gary Patmore had detuned his wingtips – a risky procedure on a glider that was giving indications of being inherently pitch instable. He was thermalling above the peak when the nose of the glider pitched up violently. He swung his weight to initiate a turn, but the glider was stalled. It fell through and the nose tucked under. It tumbled forward several times, then broke, clapping its wings around the pilot. Patmore was trapped in the falling wreckage. His arms pinned. He was unable to throw his parachute as he plummeted toward the mountain.

At the very last instant, with the: superhuman effort that only mortal fear can provide, Patmore ripped his arms free and hurled his parachute. The canopy burst open just before impact. It saved his life but he hit hard against the rocks. With a broken ankle, injured back and a lacerated face, he lay in agony alone on the peak until a helicopter rescued him.

That autumn, two local pilots received the scares of their lives. Richard Smith bought a parachute and flew with it for the first time in a flight off Coyote. He threw it when turbu1ence tumbled his glider. It saved his life. Garland Rhodes, last in a string of pilots and alone at launch above Lee Vining, was slammed into the grouhd by turbulence a moment after he took off. He lay with a broken neck through the night waiting for help.

The 1979 competitions demonstrated with utter finality that the forces of the Owens Valley must be recognized and at all costs, respected. During the Open, a pilot found himself low and about to land. Then he noticed a dust devil snaking up the foothills nearby. In a wild gamble, he attemptedto ride it up the mountain. He entered it within meters of the mountain’s craigs, but after two successful turns he was spit out and hurled with great force into the jagged rocks. The coroner reported that nearly all the bones in his body had been shattered.

In the Classic, John Davis encountered incredible turbu1ence above White Mountain. Nothing he did could keep his Ultralite Products Mosquito right-side-up. Suddenly he found himself inverted and diving at the peak. Terrified, he threw his parachute. It successfully deployed but to his horror the bridle was severed by a flying wire! The parachute drifted away in the wind but, luckily, the force of deployment had righted the glider and it resumed flying. He managed to reach the highway and land. Then he packed it up, withdrew from the contest, and left the valley.

Eric Raymond, flying his Manta Voyager three kilometers beyond Montgomery Pass off the northern end of the Whites, became engulfed in powerful lift at an altitude of six kilometers. He pulled the control bar all the way in and tried to fly out of the lift, but he kept going up!

“Suddenly, the bar was ripped out of my hands,” Eric said. “The vario swung upwards. I felt as if my arm was broken from its collision with the downtube!” Eric escaped the lift, but he has made a practice of always flying with oxygen in the Owens Valley.

During the 1980 competitions, four pilots were forced down in the White Mountains by strong winds. A French pilot stalled while making passes at takeoff and crashed. One pilot was sucked into a deep canyon and barely made it out the mouth. Then, after the Classic, an intermediate pilot attempting to launch off rocky Mazourka Peak near Independence was flipped over by a sudden dust devil. Tragicly, his back was broken and he was paralyzed for life.

Shortly before the 1981 Open an intermediate female pilot on her first Owens Valley flight broke her arm when she misjudged the wind gradient at landing.

The first day of the Open, Dick Cassetta launched into a dust devil that he did not see. The devil was so powerful that it flipped Cassettals Comet over on its back. He executed a full loop sixty meters above take-off in front of the entire field of contestants. His trajectory brought him back into the dust devil which this time knocked him into a vertical wingover. Dick recovered safely, but many at launch felt it could easily have been different.

Coming in for a landing in the heat of the afternoon, pilot Fred Hutchenson was hit by a gust and dragged along a barbed wire fence. His leg was cut to the bone and he had to withdraw from the contest.

During the Qualifier, scorekeeper Liz Sharp, flying as a contestent on her Atlas, encountered the suddenly changing conditions that so typify the often unpredictible nature of the 0wens Valley. Only a few minutes after she had launched, the wind strengthened out of the north into a powerful gust front. The windstorm brought her straight down from a high altitude. She neared the ground above a boulderfield on the upper alluvial fan. To her horror, she realized that she would have to land flying backward at twenty kilometers per hour. With her wings rocking wildly, she managed to slam the glider into the ground with the nose pointed into the wind. Over an area of many square kilometers, other pilots were forced to make similar landings.

The extreme conditions of the Owens Valley have provided the world’s formost testing ground for the evolution of hang gliding design. In less than a decade the hang glider has progressed from the basic inefficient Rogollo to today’s superb soaring wings that are capable of out-climbing sailplanes and exceeding 266 kilometers in a single flight.

The predictions of a great number of deaths in the Owens Valley from hang gliding accidents have proved false, due in part to the great sophistication of the modern wings and the respect of the pilots who fly the Owens Valley. In fact, if the proper level of respect had been exercised by all pilots to date, there would have been no deaths and only a few injuries. Let us learn from the lessons of others and avoid our own mistakes as we make the Owens Valley the world’s formost aeriel playground.

— from a three-part series by Rick Masters published in BHGA “Wings” Magazine – United Kingdom, May, June and July, 1981